Congratulations to

Cooling technology

Picture: The Linde Group; iStock.com/Valentyn Volkov

Picture: The Linde Group; iStock.com/Valentyn Volkov

Bavaria without a cold beer? Unthinkable! But chilling drinks such as beer was actually very difficult until 1875, when the first viable refrigeration machine was developed by a young engineer called Professor Carl Linde from what was later to become the Technical University of Munich (TUM). His invention led to the creation of a global enterprise and still shapes everyday life today – with cold beer and a whole lot more besides.

Until almost the end of the nineteenth century, breweries were carting huge volumes of ice from the mountains to Munich every winter – in warmer years all the way from the alpine region of Tyrol. They needed to ensure low temperatures for the production and storage of their beer – which still often went sour in the summer. Unsurprisingly, then, some of them were keen to support young mechanical engineering professor Carl Linde from what was then the Polytechnic School of Munich when he made his first forays into refrigeration technology around 1870. His complex and cost-intensive experiments in this previously almost unresearched area were inspired by a single aim: to build a cooling machine that would be actually viable for industrial use. Linde had calculated that it would be cheaper to produce ice with a machine than obtain it from natural sources – as long as he could achieve the right degree of mechanical efficiency.

Although some cooling machines were already in existence, they barely reached a fifth of the performance physically possible. In its very first trial, Linde’s initial prototype already doubled the existing efficiency benchmark. By 1875, the engineer had refined his system ready for delivery to the Dreher Brewery in Trieste. It was so robust and easy to use that industrial demand soon soared.

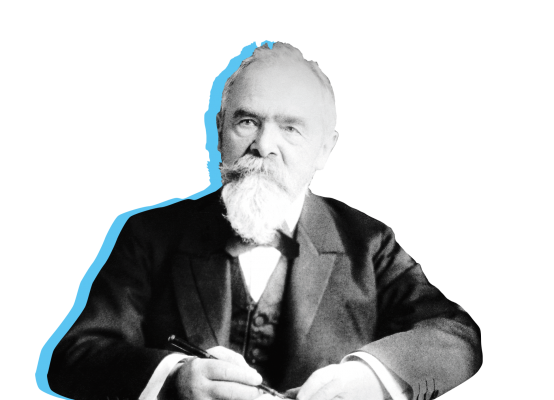

This machine is the forerunner of today’s refrigerator. Through this and his many other inventions, Carl Linde changed the world – impacting everything from the food trade through medicine to research. These innovations continue to shape our lives to this day. In recognition of his achievements, Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria, gave the inventor a noble title in 1897, so he became Carl von Linde from then on.

Linde’s compression chiller and the modern refrigerator work along the same lines. They use the physical effect known as the latent heat of vaporization, which happens when a substance changes from the liquid to the gas phase. A liquid compressed gas (the refrigerant) evaporates, thus extracting energy in the form of heat from its surroundings. As a result, the surroundings cool down. In line with the first law of thermodynamics, however, the energy is not lost, instead setting the gas atoms of the coolant in motion.

Carl Linde was TUM’s first scientist to found a company based on his invention. In 1879 he called his start-up “Gesellschaft für Lindes Eismaschinen” (Linde’s Ice Machine Company) – now the global enterprise Linde AG. To pursue his business interests, he even gave up his professorship, which for him was the “ultimate professional achievement” to pursue his business interests. He did, however, later return to the university as an honorary professor. By 1890, his company had supplied one thousand refrigeration machines to customers including breweries, dairies, chocolate factories, slaughterhouses and even artificial ice rinks. Linde also devoted some of its assets to furthering research and education, for instance making a large endowment towards the initial capital to establish the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

If air is cooled sufficiently, this gas – or gas mixture, to be precise – also becomes liquid. This occurs at ‑189°C. Linde’s company laboratory first achieved large-scale air liquefaction in 1895. Once again, although Linde was not the first to liquefy air, his process was the first one viable for industrial-scale use. Since the individual gases in air have different boiling points, they can be precisely separated. So Linde’s company also started selling gases. The metal industry needed oxygen for welding, nitrogen went into fertilizers and explosives, and airships flew on hydrogen. Plus the new electric light bulbs were filled with noble gases such as argon. Indeed, many processes in industry today would not be possible without industrial gases.

“If the natural scientist’s calling is to work completely liberated from the constraints of practical applications, then the engineer’s mission is to apply those findings and insights to a diverse range of practical scenarios.”

Carl von Linde, Professor of Theoretical Machine Research at the Polytechnic School of Munich from 1868 and founder of today’s Linde AG

Bild: The Linde Group