Congratulations to

An engine fit for the world

Picture: Deutsches Museum, München

Picture: Deutsches Museum, München

Today’s ocean liners, heavy goods vehicles and backup power generators all have one thing in common – they are generally powered by a diesel engine. Rudolf Diesel’s invention has been driving the world since 1893 – and its roots can be traced back to his studies at what would later become the Technical University of Munich (TUM), and a fire piston.

When Rudolf Diesel got his hands on a fire piston during a physics class in school, he was thrilled. At first glance, the device looks like a small bicycle pump, but when you push the piston firmly into it, it produces a flame. As a boy, Diesel was fascinated by this technology. Compression alone heats the air inside – and to such a degree that a piece of tinder in the cylinder base ignites. Decades later, he would apply this principle when designing the engine the whole world now knows by his name.

A few years after this first experience with the fire piston, Diesel learned something astonishing during his mechanical engineering studies: In a lecture at TUM’s forerunner, the Technische Hochschule München, his professor Carl von Linde explained that the steam engine, a common form of transport at the time, only harnessed a very small amount of the energy available to it. From then on, Diesel was driven by the idea of building a more efficient drivetrain system.

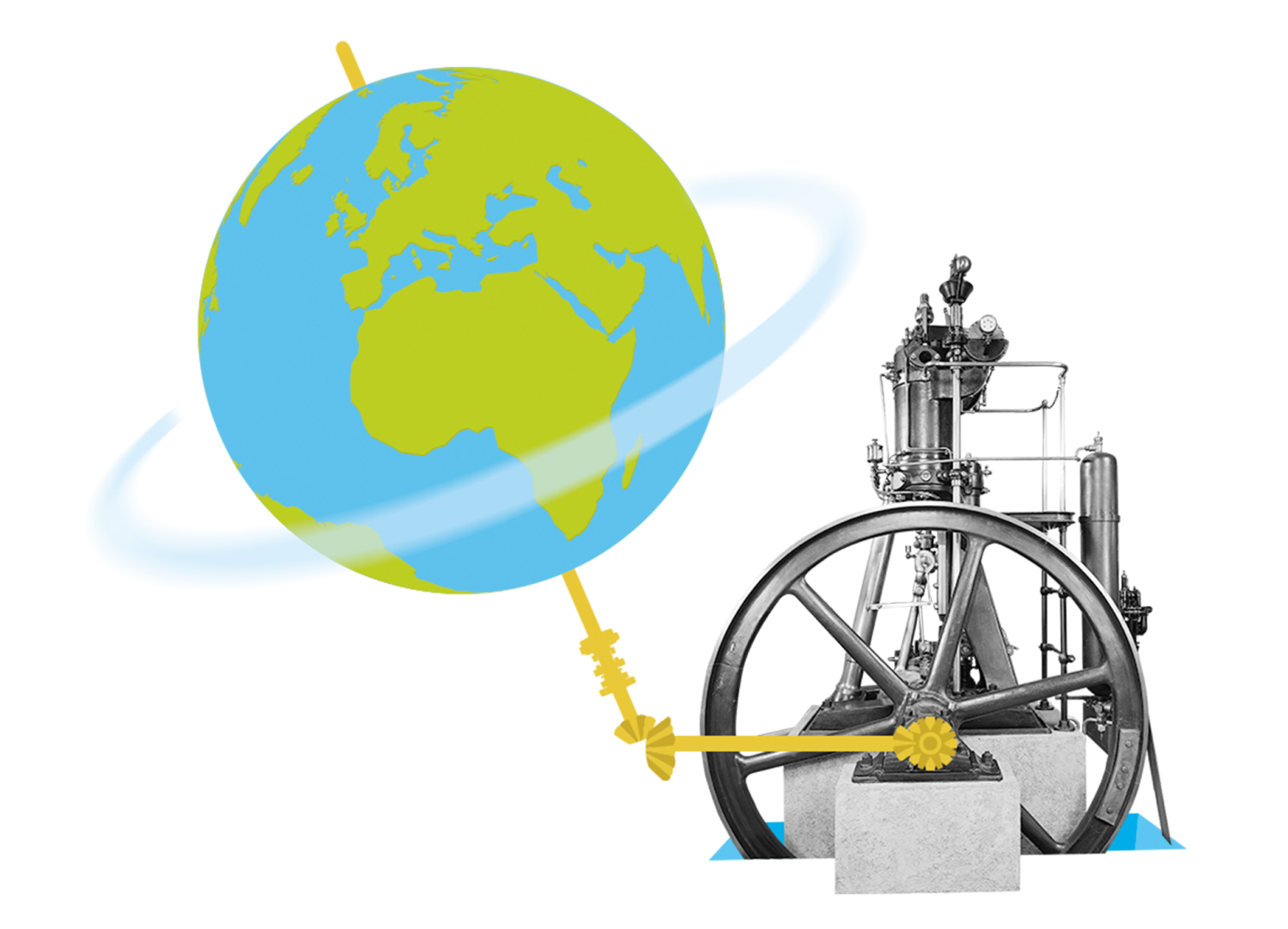

After years of trial and error, Diesel’s vision ultimately became reality. In 1893, German mechanical engineering company Maschinenfabrik Augsburg (later MAN) started building a prototype of his engine. Just a few years later, it also found a market in the US and Switzerland. To this day, the diesel engine drives our world, despite the controversy around exhaust fumes in traffic. It scales in size from portable three-kilowatt generators to marine engines as tall as a house, unleashing tens of thousands of horsepower.

Similar to the fire piston principle of his school days, self-ignition is a key feature of Diesel’s engine. Air is highly compressed in the engine’s combustion chamber, thus heating up. Fuel is then injected into the chamber and immediately ignites, with no need for any other agent. Although other inventors also built self-igniting engines, Diesel’s version ultimately prevailed. His very first engine was already twice as efficient as the steam engine. The prototype was continually improved over the course of lengthy test series and, in the end, Diesel founded his own factory in Augsburg for series production of his engine.

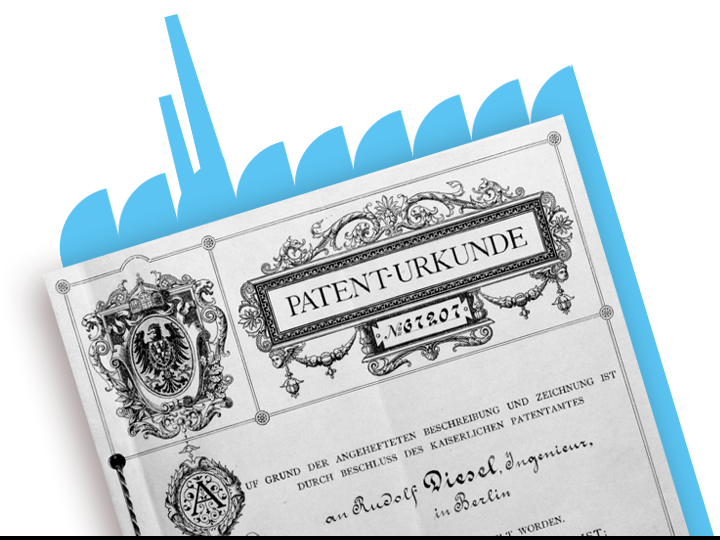

Rudolf Diesel was a particularly gifted pupil and student. In 1880, he finished his studies with the university’s best exam results to date and began work at the Parisian refrigeration and ice machinery plant run by his mentor, Carl von Linde. His path there rapidly led from apprentice straight to plant director. However, Diesel was not able to enjoy the success of his engine for long. His health suffered from his heavy workload and numerous patent disputes with other inventors. He is said to have filed more than two hundred patents himself, with registration costing him a fortune and a huge amount of time. He already shut his Augsburg engine factory back down in 1911, with ill-fated property speculation and bad company adding to his troubles. He died in mysterious circumstances in 1913.

Research on the diesel engine is still ongoing – including at TUM – with the aim of reducing nitrogen oxides and particulate matter in the exhaust gases. These hazardous substances make its use highly controversial in ever-denser city traffic. As well as filter systems, catalytic converters and new fuels for use with the diesel engine, TUM engineers are also working on completely different types of drivetrains. In 2011 and 2014, for instance, interdisciplinary collaboration resulted in the MUTE and Visio.M prototypes – two efficient electric vehicles for urban use. However, since advances to the diesel engine have continued ever since its invention, it is still comparatively efficient even now and emits relatively little CO₂. For the foreseeable future, at least, it looks set to remain important – in industry, shipping and agricultural vehicles, for example, as well as alongside the electric motor in hybrid drivetrains for road traffic.

“Just look at the long, wide and exciting technology path that lies before us!”

Rudolf Diesel, 1881, to mechanical engineering students a year after his graduation from the Technische Hochschule München (now TUM)

Bild: Copyright Historisches Archiv der MAN Augsburg