Congratulations to

Gravity satellite

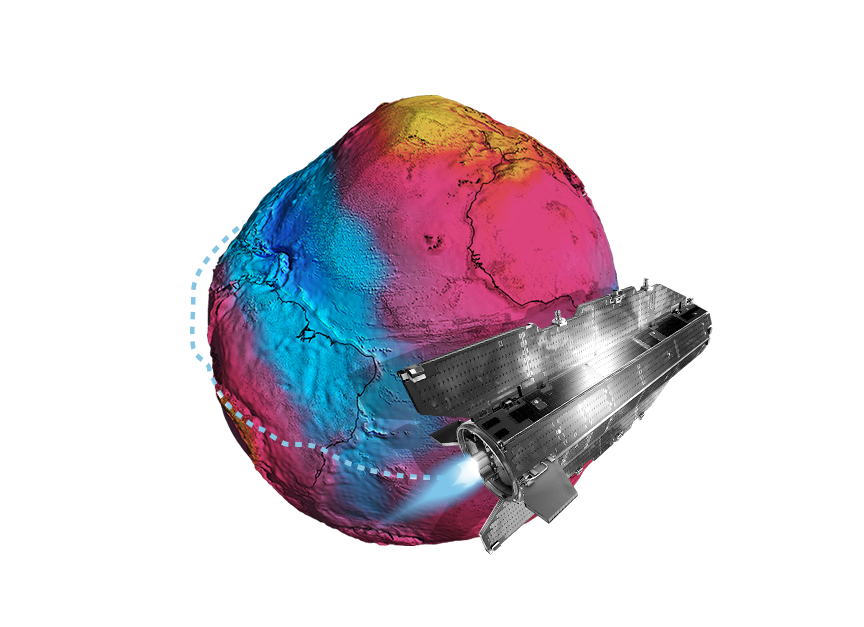

Picture: ESA / HPF / DLR, ESA–ATG-Medialab

Picture: ESA / HPF / DLR, ESA–ATG-Medialab

The plan was for a satellite to measure the gravity of our planet – and thus reveal what it looks like deep inside the Earth. Even the European Space Agency (ESA) knew it was a tall order. But a large international research team, coordinated by the Technical University of Munich (TUM), managed to do just that. Using data from outer space, the researchers were able to put together a brand new image of the Earth – and discover that it looks just like a potato.

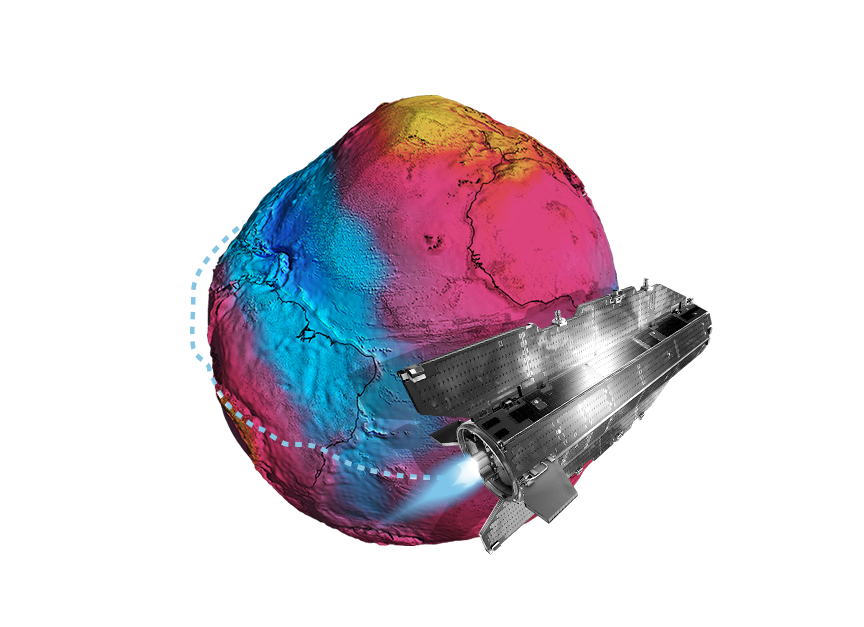

In November 2013, a satellite burned up in the sky over the Falkland Islands and dropped into the sea towards Antarctica. The Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer, known as GOCE, had reached the end of its mission. For almost five years it orbited the Earth for the European Space Agency (ESA), measuring gravity at every point on the planet – even in remote areas like the Himalayas or the plains of Antarctica, which are barely accessible on foot.

From space, the satellite sent regular data readings to the ground station. Based on these, researchers across Europe were gradually able to calculate the most accurate image ever obtained of Earth’s gravitational field: the Earth-spanning energy field that gives every object on the planet its weight and enables the Earth’s gravitational force. The analysis was coordinated by the Institute of Astronomical and Physical Geodesy at TUM.

The resulting image of the Earth is called a geoid. With all its dents, this image looks more like a potato than a sphere – because it is formed not by continents and oceans, but by the force of gravity, and that varies from place to place. These differences in the gravitational field – some of them minuscule – in turn reveal how the density of material beneath the Earth’s surface varies, since it is ultimately mass that creates gravity.

Measurement data from the GOCE plays a major role in the exploration of our planet, giving researchers around the world insights into happenings up to 200 kilometers beneath the Earth’s surface. They can thus gain a better understanding of the movement of continents and formation of mountain ranges, work out how thick the polar ice now is and map the flow of ocean currents. These findings can also be used in the quest for oil, gas and hot water for geothermal energy.

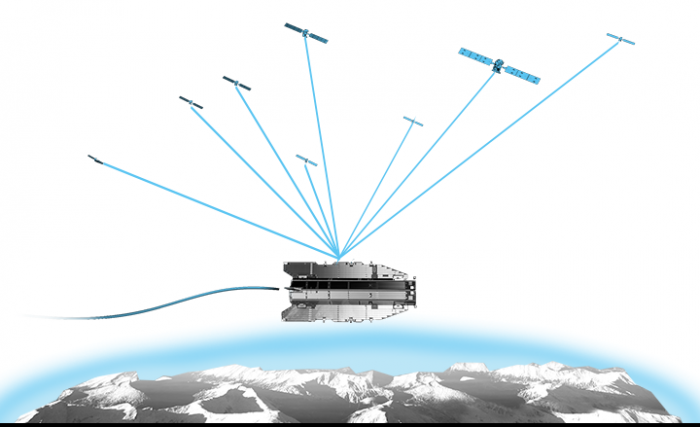

The GOCE is able to give such precise, complete gravity readings thanks to an innovative instrument that constantly measures the tiny differences in the Earth’s gravitational pull at six points on the satellite. Simultaneously, GPS was used to determine its altitude and exact position above the Earth. The research team mathematically combined the data from both measurement series to obtain gravity values for every point on the planet. One of the initiators of this experiment is a scientist at TUM: Reiner Rummel, a specialist in satellite geodesy. He successfully convinced the ESA of the scientific value of a gravity field mission and gathered support from other disciplines.

In the North Atlantic, between Greenland and Scandinavia, dense, heavy material rises from the Earth’s high-temperature mantle and forms fresh oceanic crust. It is at this point that two continental plates are drifting apart on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. GOCE’s observations from space clearly show how dense and powerful the plates are at this location. A thick red strip on the gravity map indicates especially high gravitational pull and therefore a particularly dense mass. This gives geophysicists a better indication of how far the Earth’s crust extends down into the liquid mantle here, for instance.

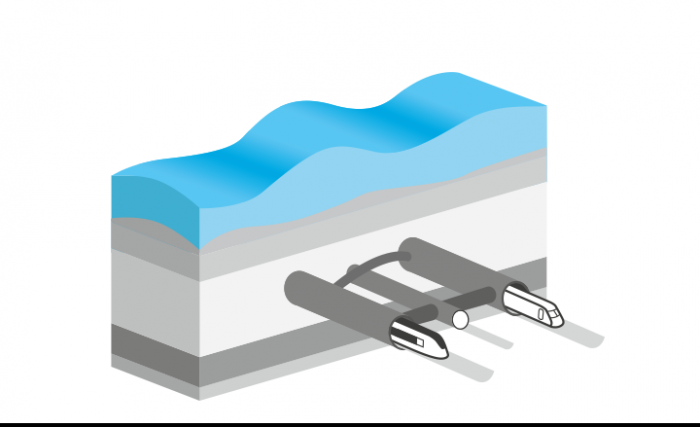

In 1988, during construction of the Channel Tunnel between England and France, the design team had to solve a huge problem: each side of the English Channel has a different sea level. Important planning data did not match up because almost half a meter separates the mean sea level of the two countries. Thanks to GOCE, such problems will soon be a thing of the past. For the first time, its satellite data makes it possible to determine a definitive sea level for any place in the world. In Europe alone there are over twenty different sea level values: Germany, for instance, bases its level on Amsterdam; France on Marseille and Austria on Trieste.

“GOCE is a prototype – we shot it up into space hoping that everything would run smoothly from day one. The fact that all the measuring systems – which are highly sensitive – are working is just fantastic. This is a splendid feat of engineering and a great success.”

Reiner Rummel, 2010, leading initiator of the GOCE gravity field mission and Professor of Astronomical and Physical Geodesy at TUM until 2011.

Picture: private

This 2011 ESA video explains and shows how the GOCE satellite measures the Earth’s gravitational field and how a so-called “geoid” is created. (Copyright: ESA)