Congratulations to

Mars Exploration Rovers

Image: Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

Image: Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

Once upon a time there was water on Mars! NASA discovered the evidence in minerals on the planet’s surface – using a method developed by a PhD student of theTechnical University of Munich half a century before. Aged just 32 at the time, Rudolf Mössbauer was awarded the Nobel Prize for this achievement.

In 2004, NASA space probes Spirit and Opportunity landed on Mars in search of clues to the history of our neighboring planet. As part of this venture, they collected rocks, analyzed them and sent the results back to Earth. During their many miles of exploration, they came across minerals that only form in the presence of water – thus proving that there must have been water on Mars at some point in time.

An essential instrument in identifying these traces was the Mössbauer Spectrometer, named after Munich physicist Rudolf Mössbauer. While working on his doctoral thesis at what was later to become the Technical University of Munich, in 1958 he discovered “recoilless nuclear resonance absorption of gamma radiation” – which he rapidly went on to demonstrate in practice.

Unknown rocks and materials – whether on Mars or Earth – can be chemically analyzed using this “Mössbauer effect”. Here, the spectrometer measures the characteristic gamma radiation scattered back by the atomic nuclei of certain elements when they are excited by a radioactive substance. In this way, the chemical compounds in the rocks can be clearly identified. In 1961, Rudolf Mössbauer – aged only 32 – was awarded the Nobel Prize for this discovery.

Mössbauer’s fellow physicist Francisco E. Fujita explains the Mössbauer effect like this: If a child tries to jump ashore from a small boat, they land in the water because the boat is thrust backwards when the child takes the leap. But if the boat is on a frozen lake, the child lands safely on the shore, because the boat cannot be propelled backwards. Instead of a boat, Mössbauer took iridium-191 atomic nuclei that emit gamma radiation. Like the child, when the gamma particle rushes away, it imparts momentum to the atom and loses some energy – enough energy so that similar atomic nuclei are no longer excited. However, if the atom is embedded in a crystal structure, it becomes like the child on the frozen lake and can take all of its energy with it. So if it now encounters a similar atomic nucleus, its energy is sufficient to excite it.

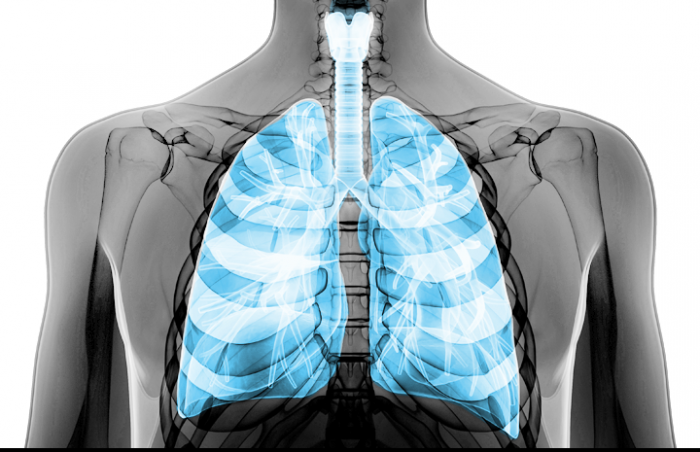

For a long time, experts could not agree whether or how exactly the vital oxygen from the air we breathe is bound to the hemoglobin in our red blood cells. From the crystalline structure of the molecule, it actually looks as though oxygen and iron atoms would not be able to join together. Yet this seemingly impossible complex of iron and oxygen is the chemical reaction that keeps us all alive, with the hemoglobin transporting oxygen from the lungs to cells around the body. And with the help of Mössbauer spectroscopy, the dispute was finally solved: This method proves that oxygen is indeed bound to the iron atom in hemoglobin.

When Rudolf Mössbauer received the Nobel Prize in 1961, he had already been working in the US for a year. Research conditions at the California Institute of Technology were significantly better than in Germany at the time. But his home university was determined to win back the Munich-born physicist, offering him a professorship in 1964. Mössbauer was keen, but imposed some conditions – calling for a restructured physics department based on the American model, with plenty of lab space and a flat hierarchy, to be located in a new building in Garching. When the Bavarian government approved the new physics faculty, the press at the time talked about a “second Mössbauer effect”. The new physics building was ultimately completed in 1970.

“Mössbauer’s discovery has been received with enormous interest. In many places, research into the Mössbauer effect is already under way. His discovery has made it possible to demonstrate the fundamental consequences of Einstein’s theory of relativity in the laboratory.”

Ivar Waller, 1961, Nobel Committee for Physics of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, from the award ceremony speech for Rudolf Mössbauer

Bild: © ®The Nobel Foundation: Photo: Lovis Engblom