Congratulations to

The pigments of life

Picture: iStock.com / photo5963

Picture: iStock.com / photo5963

Red and green are the colors that best symbolize life itself. At what is now the Technical University of Munich (TUM), chemist Hans Fischer was able to discover how red pigments in the blood and the green pigment chlorophyll in plants are structured. He even completely reproduced the blood pigment hemin in a test tube, which had long been considered impossible – and was thus awarded the Nobel Prize in 1930.

These two pigments are crucial to life on Earth, with red hemin transporting oxygen in the blood and green chlorophyll enabling photosynthesis in plants. What chemist Hans Fischer discovered was that nature has constructed both pigments in a very similar way. In his laboratory at TUM, known then as the Technische Hochschule München, he set about recreating their individual components – even managing to completely artificially produce the red blood pigment hemin in 1928. An extraordinary achievement for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry just two years later, in 1930.

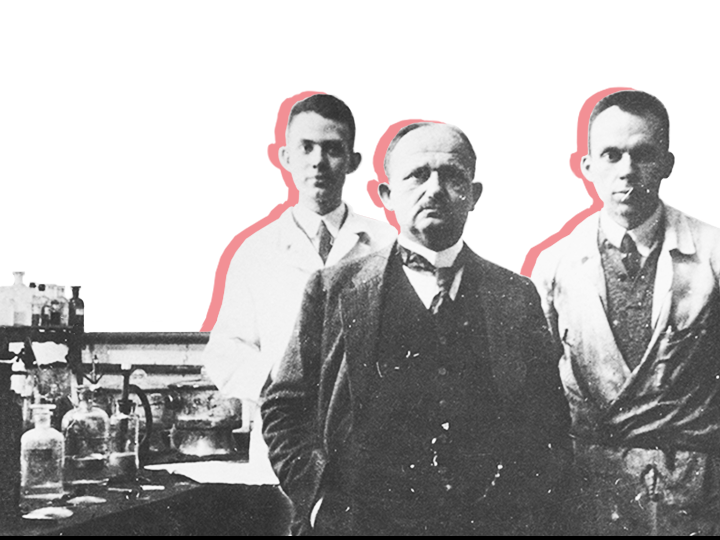

For a long time, hardly anyone believed that it was possible to replicate such a molecule at all. But Fischer, surrounded by dozens of staff, spent years working on it in his lab. Organized into two shifts and deploying almost industrial-scale process planning, they continued until their synthesis was successful. First they decoded the structure of hemin, a huge molecule consisting of seventy atoms that form a ring around an iron atom. Then they recreated this ring, known as porphyrin. And in the end, they were able to reconstruct the hemin completely.

Fischer subsequently identified almost the same blueprint in chlorophyll. Decades later, Robert Huber, also a chemist at TUM, would establish exactly how plants and other organisms use this green pigment to extract energy from sunlight – which also earned him the Nobel Prize.

Hemin transports oxygen around the body. The oxygen binds to an iron atom in the middle of the porphyrin ring, and it is this iron atom that gives hemin its red color. Chlorophyll is the substance that plants and other organisms use to absorb the sun’s energy for photosynthesis. At its center is a magnesium atom. Since the plant pigment does not use the green spectrum of sunlight, it reflects it – making the leaves appear green to our eyes. The basic structure of these two pigments is identical: a porphyrin ring.

In modern medicine, applications of natural pigments include the treatment of tumors and other tissue changes in sensitive areas such as the eye, brain and gastrointestinal tract. A precursor of the red blood pigment is used as an active ingredient in photodynamic therapy for skin cancer, for instance. This is applied as a cream to the affected area of skin. Light from a special lamp then activates the pigment for a few minutes, causing the tumor cells to die off. This treatment has almost no effect on healthy skin, and 70 to 90 percent of tumors treated heal without scarring.

Hans Fischer motivated his staff – inspiring them with his ideas and his own dedication. And he treated them as people “who worked with him rather than under him,” as one of the scientists recalled. The exceptional work ethic at his lab is well illustrated by a satirical piece from the “Nobel magazine” his students produced for him: “Harsh but final – Secret Council resolution: To ensure that my employees cannot continue to overexploit their admirable capabilities, I hereby decree that from January 1, 1931, the laboratories will be closed on weekdays from 1 a.m. to 3 a.m. Work is still permitted on Sundays, but must not exceed 24 hours.”

“This synthesis was the pinnacle of his [Hans Fischer’s] research endeavors – which, in view of both their scale and the incredible complexities associated with them, deserve to be called an epic achievement.”

Henning G. Söderbaum, 1930, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Picture: © ®The Nobel Foundation: Photo: Lovis Engblom